The Always, Onlys and Nevers of Motorcycling

We hear it all the time in our sport. Always do this, never do that, the only way is this way. So I was having a conversation with my buddy Scott about this recently where we were asking each other, what are the always, onlys and nevers of riding. We each would try to come up with an absolute and the other would try to poke holes in it.

Always do all your braking before the corner

Fear mongering is big here. The fear of sliding out. The fear of hitting gravel. The fear of the what-ifs have made this one of the most long lasting “nevers” in modern motorcycles. Honestly, I go to the brakes mid corner all the time. I’ll bet you have too. And then you kicked yourself for making such a grave mistake, right?

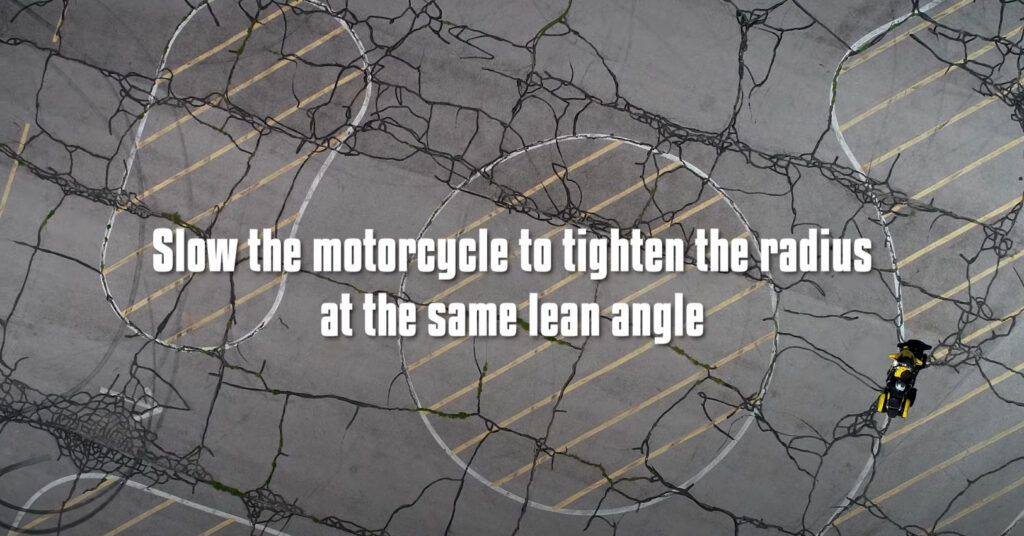

Yes, indeed, grabbing the front brake mid corner isn’t a very good idea. But what if we’re nervous and we sneak the front brake on and gently add a bit more pressure to bring our speed down, radius equals miles per hour, slowing down makes the motorcycle turn a tighter radius. Why is this still considered by many to be so dangerous? Why do “they” say that if we find ourselves in a corner going faster than we want to be going that our only option is to stay on the gas, keep going faster, and lean more? How does that make any sense? Well it doesn’t. If we feel like were going too fast in a corner, going faster isn’t going to solve the problem. It’ll just end the anticipation.

So, yes, we can use the front brake in a corner. Yes, we can go to the brakes in the middle of the corner. We should be going to the brake whenever we are nervous, but the key here is to go to the brake with finesse. Sneak the front brake on, don’t drop anchor. Be ever mindful of our 100-points of grip.

Never add lean angle and throttle at the same time

This is one of those situations that’s a rule – with exceptions. Ordinarily, it’s just not a good idea to add throttle to lean angle. Especially when grip is down or the pace is up. Remember when we accelerate, our rake and trail numbers change, our wheelbase extends, and we’re asking the bike to run wider. But… if we’re trying to add lean angle, we’re trying to make the radius tighten. So why would we push two competing inputs against each other? Turns out, there are a few very specific places and times to bend this rule a little. For example, we’re chasing lap records and we need an extra tenth or two from a chicane.

It becomes a calculated risk. Suddenly that 100 points of grip is back in the front of our minds… “just how much throttle can I sneak in here, and how do I cheat lean angle just enough?” We’re also thinking about weight transfer. If we’re asking the front tire to turn us, we should really have load up front… but if we’re accelerating, all that weight goes rearward.

So is an unloaded front tire and sending the bike conflicting signals a good practice for everyday riding? Probably not. Can we play with this to get closer and closer to using all 100 points of grip? Yes, so long as we do so smoothly and we’re ready for the consequences of overcoming that 100th point.

The only way to turn is with counter steering

With counter steering, we are managing the gyroscope. If we are on the gas, actively accelerating, to stay on-line we need to add more lean. Now, we can affect lean by pushing down on our foot pegs, but the problem here is efficiency. When we move our upper bodies off the inside of the bike’s centerline on corner entry it helps the bike lean, but also this naturally adds pressure to the bars – enough to counter steer subtly. If we need to change direction quickly, this isn’t a great way to get that tire deflected. This subtle counter steering gets the process of deflecting the tire started, but the most efficient way of doing this is consciously counter steering at the bars .

The fun part: once that tire is deflected, we can control that rate of lean with how we move our bodies and with how much weight arrives on that inside foot peg. Or, we can simply continue to counter steer. The problem with simply continuing to push: if we still have pressure on the bars, the steering head isn’t swinging into the corner and actually steering the motorcycle. The truth here is there are lots of things we can do to affect direction change on the bike, the best riders understand this and use a combination of all these techniques. Not just one of them. Like so many things, the pressing issue is that first and last five percent of our input. (See what I did there?)

Never Apex on a Public Road

First, let’s clear up a definition so we’re all on the same page: An apex is simply the point at whichwe are closest to the inside of the turn. On public roads we need to think about the risks of apexing on the yellow line. Is that really where we want to put our motorcycle, with our head in the oncoming lane? Also, apexes on the road are often hard to discern, so why even obsess about the “apex” on the street?

The reality is we will all be closer to the inside of a corner at some point in a turn, so like it or not, we are all “apexing” on the street. But putting ourselves in a position to see the exit is considerably more important. This is what Champ School would call the decision point. Everything we do on a bike is to get into the corner, to the decision point, get the bike turned or pointed, to see what is happening or to see the corner exit. The apex is just a thing we can use to help us do all of that.

You’ll Never run out of clearance on a sport bike

Apparently, according to many, we only really need to worry about limited corning clearance on a cruiser, and thus, we should be riding these two different styles of bikes in two very different way. I’m sorry, but every bike has a lean angle limit, on some bikes it might be the foot pegs or floorboards, on others it might be the edge of the tire. What’s more, lean equals risk, right.

The more we lean the more risk we are taking. So counter-leaning with the assumption that we’ll never run out of corning clearance may have limited value based on how fast we might be going. It’s probably better to find ways to reduce lean, reduce risk, instead of just hucking the bike over on it’s side and trusting we’ll never run out of clearance.

Never stab the brakes

For sure, this is a habit that we do not want to form, but when we’re going slow and the grip is good, nothing matters. Sure, I can get away with stabbing the brakes when I’m straight up and down, trundling along in a parking lot on a warm day, but why would I want to? This one probably has a bit of value, yeah?

Never push the throttle against the front brake

How do “mixed messages” work in other parts of your life? If we’re using the front brake we’re telling the bike we want to slow down and turn. When we’re using the throttle, we’re telling the bike that we want to speed up and go straight.

This is one is pretty valid, and if you don’t believe me, here’s Sylvan Guintoli telling us to never push the throttle against the front brake.

Also, here’s what the guys over at Champ School had to say about it.

Pushing the throttle against the front brake is giving the motorcycle conflicting instructions. Now that might work in a parking lot, but probably won’t work in the real world. So lets try not to overlap those two controls. Cool?

Conclusion

Now look, the point of all of this isn’t to make excuses for using poor techniques. There are well understood best practices that we should be gravitating towards. The point we are trying to make here is that we need to be cautious of absolutes. If you’ve taken ChampU, they say one of the seven reasons riders crash is not adjusting to change. Not being adaptable, right? So much of what I advocate for is to set ourselves up to be able to adapt, to adjust to constantly changing conditions. Not riding by rote. A pre-defined set of unbreakable rules.

The idea of being “efficient;” using the right control at the right time, has a place here. If we’re efficient with controls, we have more mental bandwidth to deal with the unexpected. There is a big difference between “is this possible” and “is this a good idea” or even “is this the best way to accomplish this task?” Best practices, by definition, are the best way to do something.

We should try not to think in terms of rules or of absolutes, instead think in terms of objectives. The Umbrella of Direction, the Decision Point. Getting the motorcycle slowed down, getting the motorcycle turned, getting the motorcycle stopped, reducing lean, reducing risk, staying within our 100-points of grip, maintaining our focus.

So, instead of thinking about “Hey, I need to be in second gear here, and tip in there, or I’m at the corner, I need to be on the gas now!” we should be thinking about using our controls, understanding what each of our controls do, what we can do with our bodies, and our eyes, to affect the motorcycle, to put the bike where we want it to be.